Classic Poems About Seeing Someone Again

"God Speed" by Edmund Leighton

10 Greatest Love Poems Ever Written

by Conrad Geller

People are always asking "What are the best love poems?" or "Where tin I find something cute to say to the woman I love?" or "…to the man I love?"

If you are looking for honey poems in more modernistic language, you volition probably detect the ten Best Love Poems of 2021 useful. If you like a more classical style, well, here I am again, unbowed past the heartfelt, sometimes urgent suggestions for altering my recent "ten Greatest Poems almost Expiry." This time I choose a topic—beloved—less grim if equally compelling. These should quench your thirst for the best love poems, but don't take these as some kind of how-to manual in your relationship. Similar death, dear seems to be something most poets know little almost; for prove, run into their biographies. The poems I have chosen this fourth dimension cover the total spectrum of responses to love, from joy to anguish, and sometimes a mixture of both. Equally befits the topic this time, the list is a fleck heavy on Romantics and low-cal on those rational Enlightenment types. Here, with a few comments and no apologies, is the listing:

Related Content

ten Best Love Poems of 2021

10 Greatest Poems Ever Written

x. "Since There's No Help," by Michael Drayton (1563-1631)

It may be a bad augury to begin with a poem by a loser, but there information technology is. Drayton, a contemporary and possible acquaintance of the Bard, evidently had come to the unhappy stop of an affair when he penned this sonnet. He begins with a show of stoic indifference: ". . . you get no more than of me," but that tin't last. In the last 6 lines he shows his true feelings with a series of personifications of the dying figures of Love, Passion, Faith, and Innocence, which he pleads can exist saved from their fate by the lady's kindness.

Michael Drayton

.

Since In that location's No Aid

Since there'southward no assistance, come allow us kiss and part;

Nay, I have done, y'all get no more of me,

And I am glad, yea glad with all my heart

That thus and then cleanly I myself can complimentary;

Shake hands forever, cancel all our vows,

And when we meet at any time once again,

Be it not seen in either of our brows

That we i jot of old dearest retain.

Now at the terminal gasp of Love's latest jiff,

When, his pulse failing, Passion speechless lies,

When Faith is kneeling by his bed of decease,

And Innocence is closing up his eyes,

Now if thou wouldst, when all have given him over,

From expiry to life one thousand mightst him withal recover.

.

.

9. "How Do I Love Thee," by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861)

If verse, as Wordsworth asserted, is "emotion recollected in quiet," this sonnet scores high in the old essential only falls brusk of the latter. Elizabeth may have been the original arts groupie, whose passion for the famous poet Robert Browning seems to have known no limits and recognized no excesses. She loves she says "with my childhood'due south faith," her beloved now holding the place of her "lost saints." No wonder this poem, whatsoever its hyperbole, has long been a favorite of boyish girls and matrons who recall what it was like.

.

How Practise I Dear Thee?

Browning

How do I love thee? Let me count the means.

I love thee to the depth and latitude and summit

My soul can attain, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and platonic grace.

I love thee to the level of every day's

Well-nigh quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for correct.

I dearest thee purely, every bit they plough from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my quondam griefs, and with my babyhood's faith.

I honey thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall merely honey thee better later death.

.

.

8. "Love's Philosophy," by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

In spite of its title, this very sweet sixteen-line verse form has nix to do with philosophy, as far every bit I can meet. Instead, it promulgates one of the oldest arguments of a swain to a maid: "All the world is in intimate contact – water, current of air, mountains, moonbeams, even flowers. What near you lot?" Since "Nothing in the world is single," he says with multiple examples, "What is all this sweet work worth / If thou buss not me?" Interestingly, the lover's proof of the "law divine" of mingling delicately omits whatsoever reference to animals and their mingling beliefs. In any case, I promise it worked for him.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

.

Love'south Philosophy

The fountains mingle with the river

And the rivers with the ocean,

The winds of heaven mix for always

With a sweet emotion;

Zip in the world is single;

All things past a constabulary divine

In 1 spirit run across and mingle.

Why not I with thine?—

Run across the mountains kiss high sky

And the waves squeeze i another;

No sister-flower would be forgiven

If it disdained its brother;

And the sunlight clasps the earth

And the moonbeams kiss the sea:

What is all this sweet work worth

If thou buss non me?

.

.

vii. "Dearest," past Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

Here nosotros have some other bold effort at seduction, this i much longer and more than complicated than Shelley's. In this poem, the lover is attempting to proceeds his desire past highly-seasoned to the tender emotions of his object. He sings her a song about the days of knightly, in which a knight saved a lady from an "outrage worst than decease" (whatever that is), is wounded and eventually dies in her artillery. The poet's beloved, on hearing the story, is securely moved to tears and, to make the story not every bit long equally the original, succumbs.

As with his virtually famous poem, "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner," Coleridge employs the oldest of English forms, the ballad stanza, but here he uses a lengthened 2nd line. Coleridge, past the way, could really tell a romantic story, whatever his ulterior motives.

.

Love

Coleridge

All thoughts, all passions, all delights,

Whatever stirs this mortal frame,

All are but ministers of Dearest,

And feed his sacred flame.

Oft in my waking dreams do I

Live o'er again that happy hour,

When midway on the mount I lay,

Beside the ruined tower.

The moonshine, stealing o'er the scene

Had blended with the lights of eve;

And she was at that place, my hope, my joy,

My ain love Genevieve!

She leant against the arméd man,

The statue of the arméd knight;

She stood and listened to my lay,

Amid the lingering low-cal.

Few sorrows hath she of her own,

My promise! my joy! my Genevieve!

She loves me best, whene'er I sing

The songs that make her grieve.

I played a soft and doleful air,

I sang an former and moving story—

An old rude song, that suited well

That ruin wild and hoary.

She listened with a flitting chroma,

With downcast optics and modest grace;

For well she knew, I could not choose

But gaze upon her confront.

I told her of the Knight that wore

Upon his shield a burning make;

And that for ten long years he wooed

The Lady of the Land.

I told her how he pined: and ah!

The deep, the low, the pleading tone

With which I sang another's love,

Interpreted my own.

She listened with a flitting blush,

With downcast eyes, and modest grace;

And she forgave me, that I gazed

Too fondly on her face!

Simply when I told the cruel scorn

That crazed that bold and lovely Knight,

And that he crossed the mountain-woods,

Nor rested mean solar day nor night;

That sometimes from the vicious den,

And sometimes from the darksome shade,

And sometimes starting up at in one case

In dark-green and sunny glade,—

There came and looked him in the confront

An angel beautiful and vivid;

And that he knew it was a Fiend,

This miserable Knight!

And that unknowing what he did,

He leaped amid a murderous ring,

And saved from outrage worse than death

The Lady of the Land!

And how she wept, and clasped his knees;

And how she tended him in vain—

And ever strove to expiate

The scorn that crazed his brain;—

And that she nursed him in a cave;

And how his madness went away,

When on the yellowish forest-leaves

A dying man he lay;—

His dying words—but when I reached

That tenderest strain of all the ditty,

My faultering voice and pausing harp

Disturbed her soul with pity!

All impulses of soul and sense

Had thrilled my guileless Genevieve;

The music and the doleful tale,

The rich and balmy eve;

And hopes, and fears that kindle hope,

An undistinguishable throng,

And gentle wishes long subdued,

Subdued and cherished long!

She wept with pity and delight,

She blushed with dear, and virgin-shame;

And like the murmur of a dream,

I heard her breathe my proper noun.

Her bosom heaved—she stepped bated,

As conscious of my look she stepped—

And so suddenly, with timorous eye

She fled to me and wept.

She half enclosed me with her arms,

She pressed me with a meek embrace;

And bending back her caput, looked upwardly,

And gazed upon my face.

'Twas partly beloved, and partly fear,

And partly 'twas a bashful art,

That I might rather experience, than see,

The swelling of her heart.

I calmed her fears, and she was calm,

And told her love with virgin pride;

So I won my Genevieve,

My vivid and beauteous Helpmate.

.

.

6. "A Red, Red Rose," past Robert Burns (1759-1796)

Burns' best-known poem as well "Auld Lang Syne" is a elementary declaration of feeling. "How beautiful and delightful is my dearest," he says. "Yous are then lovely, in fact, that I will love you lot to the end of time. And even though we are departing at present, I volition return, no matter what." All this is expressed in a breathtaking backlog of metaphor: "And I will love thee still, my honey, / Till a' the seas gang dry." This poem has no peer equally a elementary cry of a young human who knows no boundaries.

Robert Burns

.

A Red, Red Rose

O my Luve is like a scarlet, scarlet rose

That's newly sprung in June;

O my Luve is like the melody

That's sweetly played in tune.

So fair art thou, my bonnie lass,

Then deep in luve am I;

And I will luve thee yet, my beloved,

Till a' the seas gang dry.

Till a' the seas gang dry, my beloved,

And the rocks cook wi' the sun;

I will honey thee all the same, my love,

While the sands o' life shall run.

And fare thee weel, my merely luve!

And fare thee weel awhile!

And I will come over again, my luve,

Though it were ten thousand mile.

.

.

5. "Annabel Lee," by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

Poe shows off his amazing talent in the manipulation of language sounds here, perchance his best-known poem afterward "The Raven." It'south a festival of auditory effects, with a delightful mixture of anapests and iambs, internal rhymes, repetitions, assonances. The story itself is a Poe favorite, the tragic decease of a cute, loved daughter, died after her "high-built-in kinsman" separated her from the lover.

.

Edgar Allan Poe

Annabelle Lee

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the body of water,

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee;

And this maiden she lived with no other idea

Than to beloved and be loved by me.

I was a child and she was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea:

Merely we loved with a dear that was more than love—

I and my Annabel Lee;

With a dearest that the winged seraphs of heaven

Laughed loud at her and me.

And this was the reason that, long agone,

In this kingdom by the bounding main,

A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling

My beautiful Annabel Lee;

And then that her highborn kinsman came

And bore her away from me,

To shut her up in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the sea.

The angels, not half so happy in heaven,

Went laughing at her and me—

Yep!—that was the reason (every bit all men know,

In this kingdom by the sea)

That the wind came out of the cloud past night,

Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.

But our love information technology was stronger past far than the love

Of those who were older than we—

Of many far wiser than we—

And neither the laughter in heaven higher up,

Nor the demons downwardly under the bounding main,

Tin can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee:

For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams

Of the cute Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

Then, all the nighttime-tide, I lie downwardly by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre at that place by the sea,

In her tomb past the sounding body of water.

.

.

4. "Whoso List to Hunt," by Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542)

Supposedly written about Anne Boleyn, married woman of King Henry VIII, this bitter poem compares his dear to a deer fleeing before an exhausted hunter, who finally gives up the chase, because, as he says, "in a net I seek to agree the wind." Also, he reflects, she is the king'south property, and forbidden anyway. The bitterness comes mainly in the first line: "I know where there is a female deer, if anyone wants to become afterwards her." Some of the tougher vocabulary is translated beneath. Every bit the history goes, she could non produce the male person heir Henry wanted and he (probably) wrongfully defendant her of incest and adultery simply and so he could have her executed. This love, hijacked past college forces, painfully elusive, and wildly tempting is exquisitely real and compelling.

.

Whoso List to Hunt

Wyatt

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind,

But equally for me, alas, I may no more than.

The vain travail hath wearied me so sore,

I am of them that farthest cometh backside.

Yet may I past no means my wearied mind

Depict from the deer, but as she fleeth afore

Fainting I follow. I leave off therefore,

Since in a internet I seek to hold the wind.

Who listing her hunt, I put him out of dubiousness,

Too as I may spend his fourth dimension in vain.

And graven with diamonds in letters plain

There is written, her fair neck circular about:

"Noli me tangere, for Caesar'south I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame."

Whoso list: whoever wants

Hind: Female deer

Noli me tangere: "Don't affect me"

.

.

three. "To His Coy Mistress," by Andrew Marvell (1621-1678)

All the same another seduction attempt in poesy, perhaps this poem doesn't belong on a list like this, since information technology isn't well-nigh honey at all. The lover is trying to convince a reluctant ('coy") lady to accede to his importuning, not by a sad story, as in the Coleridge poem, or past an appeal to nature, as in Shelley, only by a formal argument: Sexuality ends with death, which is inevitable, then what are you saving it for?

. . . so worms shall endeavor

That long preserved virginity,

And your quaint honour turn to dust,

And into ashes all my animalism.

and it ends with the pointed proposition,

Permit us scroll all our force and all

Our sweetness up into one brawl,

And tear our pleasures with rough strife

Thorough the fe gates of life.

This is one of the ten best poems in the English language, and so I'll include it hither, whether it can be strictly pinned down with a characterization like love or death or not.

.

To His Coy Mistress

Marvell

Had nosotros but earth enough and time,

This coyness, lady, were no crime.

Nosotros would sit down, and think which way

To walk, and pass our long beloved's day.

Thou by the Indian Ganges' side

Shouldst rubies find; I by the tide

Of Humber would complain. I would

Honey you lot 10 years before the flood,

And y'all should, if you please, refuse

Till the conversion of the Jews.

My vegetable love should grow

Vaster than empires and more wearisome;

An hundred years should go to praise

Thine eyes, and on thy brow gaze;

Two hundred to admire each breast,

Simply thirty thousand to the remainder;

An age at least to every part,

And the last historic period should show your heart.

For, lady, you deserve this state,

Nor would I love at lower charge per unit.

Merely at my back I always hear

Time's wingèd chariot hurrying near;

And yonder all before the states lie

Deserts of vast eternity.

Thy beauty shall no more be found;

Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound

My echoing vocal; then worms shall try

That long-preserved virginity,

And your quaint honour plough to dust,

And into ashes all my lust;

The grave's a fine and individual place,

But none, I retrieve, do there comprehend.

At present therefore, while the youthful hue

Sits on thy skin similar morning dew,

And while thy willing soul transpires

At every pore with instant fires,

Now allow us sport us while we may,

And now, like amorous birds of casualty,

Rather at once our time devour

Than languish in his slow-chapped power.

Let u.s. curl all our strength and all

Our sweetness upwardly into one ball,

And tear our pleasures with rough strife

Through the iron gates of life:

Thus, though nosotros cannot make our sun

Stand still, yet we will brand him run.

.

.

2. "Bright Star," by John Keats (1795-1821)

Keats brings an almost overwhelming sensuality to this sonnet. Surprisingly, the kickoff eight lines are not about love or fifty-fifty human life; Keats looks at a personified star (Venus? But it'southward non steadfast. The Due north Star? It's steadfast but not particularly brilliant.) Whatsoever star it may exist, the sestet finds the lover "Pillow'd upon my fair love'due south ripening breast," where he plans to stay forever, or at least until death. Somehow, the surprising juxtaposition of the wide view of earth as seen from the heavens and the intimate moving picture of the lovers works to invest the scene of dalliance with a cosmic importance. John Donne sometimes achieved this same issue, though none of his poems fabricated my terminal cut.

John Keats

.

Bright Star

Bright star, would I were stedfast as chiliad art—

Non in lone splendour hung aloft the nighttime

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature's patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth'southward human being shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snowfall upon the mountains and the moors—

No—yet still stedfast, yet unchangeable,

Pillow'd upon my off-white dear's ripening breast,

To feel for always its soft autumn and neat,

Awake for ever in a sweetness unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And and then live ever—or else swoon to expiry.

.

.

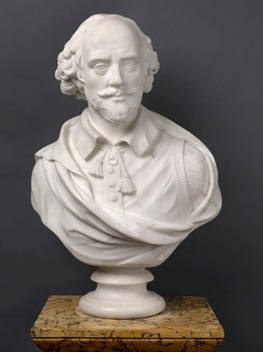

1. "Let Me Not to the Marriage of True Minds" (Sonnet 116), past William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Shakespeare

This poem is non a personal appeal but a universal definition of love, which the poet defines every bit constant and unchangeable in the face up of any circumstances. It is like the North Star, he says, which, even if we don't know annihilation else well-nigh it, we know where it is, and that's all we need. Even decease cannot lord itself over love, which persists to the end of fourth dimension itself. The terminal couplet strongly reaffirms his delivery:

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no human ever loved.

The trouble is that if Shakespeare is right nigh love'south constancy, then none of the other poems in this list would take been written, or else they're non actually nigh dearest. Information technology seems Shakespeare may be talking well-nigh a deeper layer of love, transcending sensual attraction and intimacy, something more alike to compassion or benevolence for your fellow man. In this revelation of the nature of such a force, from which mutual love is derived, lies Shakespeare's genius.

.

Sonnet 116

Let me not to the matrimony of true minds

Acknowledge impediments. Love is non dearest

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

O no! it is an e'er-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wand'ring bark,

Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken.

Dearest's non Fourth dimension's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle'due south compass come;

Beloved alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be mistake and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man e'er loved.

.

Post your own all-time honey verse form pick or list in the comments section below.

.

.

Conrad Geller is an former, mostly formalist poet, a Bostonian now living in Northern Virginia. His work has appeared widely in impress and electronically.

Notation TO READERS: If you enjoyed this verse form or other content, please consider making a donation to the Society of Classical Poets.

Annotation TO POETS: The Order considers this page, where your poetry resides, to be your residence as well, where you may invite family unit, friends, and others to visit. Feel gratis to treat this folio every bit your home and remove anyone here who disrespects y'all. Simply transport an email to mbryant@classicalpoets.org. Put "Remove Comment" in the subject line and list which comments you would like removed. The Society does non endorse whatsoever views expressed in individual poems or comments and reserves the correct to remove any comments to maintain the decorum of this website and the integrity of the Society. Please see our Comments Policy hither.

CODEC News:

Source: https://classicalpoets.org/2016/10/27/10-greatest-love-poems-ever-written/

0 Response to "Classic Poems About Seeing Someone Again"

Post a Comment